A different drummer

Perhaps surprisingly, the backgrounds of homeless people vary as much as their faces do. They are often labeled as dirty, scary or even dangerous – a class of people who have lost their sanity during their time on the streets.

Another stereotype is that they are lazy, that their homelessness is due to indolence and therefore they deserve no sympathy. We see these people every day – by the roadside, on street curbs and park benches – but we really know next to nothing about why they live the way they do.

Although the homeless are in a sense invisible to many of us, ignored and misunderstood, the phenomenon has been documented in the U.S. since the 1640s. Back then, when the first manifestations of homelessness were appearing, it was judged a moral deficiency, a character flaw.

Unfortunately, many of these attitudes haunt us today. Many believe that to escape their plight, the homeless must simply “pick themselves up” and begin living life the right way – that is, follow the American Dream. If they don’t, they are deserving of a roofless life because they offer no value to society and are not pulling their weight.

In reality, though, the displacement of people varies greatly and comes from many different causes including, as Robert Fischer of the Plymouth Congregational Church points out in an online article, “industrialization, wars and subsequent problems, natural disasters, racial inequities, medical problems, widowhood and the values of a nation as represented by their policies relating to the disenfranchised.”

Even so, society does provide various kinds of aid for escaping homelessness. So the question remains, why do some choose to continue living under such circumstances for so long? What may not be considered is that within the homeless subculture, there are those who see their lifestyle as attractive.

Ryan

I observed and interviewed several homeless people, including one young man whom I will call Ryan. In first watching him from a distance, I noticed right away that his radiant smile contradicted the preconceived notions of the people who stared at him as they passed. Far from feeling sorry for himself, he seemed to have a free spirit, living everyday on a new street corner, viewing the world as his oyster, neither seeking nor caring for sympathy from others.

Indeed, Ryan cares nothing for the approval of those around him, though he will gladly avail himself of their spare change, for that is the only thing he really cares to extract from the society that threatens to engulf him. While the idea of slavery may invoke horrible images from a past century, Ryan sees slavery all around him as rules and regulations, standards and expectations encroach more and more on the free spirit of a new generation of young people.

Ryan’s youthful humor and optimism was obvious as his antics repeatedly inclined people to help, including a cardboard sign that read, “I bet you can’t hit me with a quarter.” The only cause for his life on the streets, he told me, was his own decision to be there.

He had been an A student in high school, and it would be easy to conclude that he sank into homelessness despite his high intelligence. Ryan insists, though, that he lives as he does because of his high intellect, coupled with a higher-level view of life that compels him to part ways with a society that has drowned him in expectations he no longer cares to meet.

He and others who share his views feel blessed to have arrived at this understanding of society and the limitations it places on people. Ryan explains that he and his peers neither resent nor disrespect authority figures or those who thrive in today’s society. Those people, too, are needed; they just have a different perception of a good or successful life.

Ryan recalled his grandfather speaking with passion about his financial investments that were all held in a plan called Freedom 55.

“Is that really freedom,” said Ryan, “living 55 years in slavery to society so you can rest and wander aimlessly when you are old and frail?”

In pondering the greatest advantages of being homeless, Ryan smirked, pointed to his long blonde hair and his bland brown clothing and said, “The simplicity.”

Michael

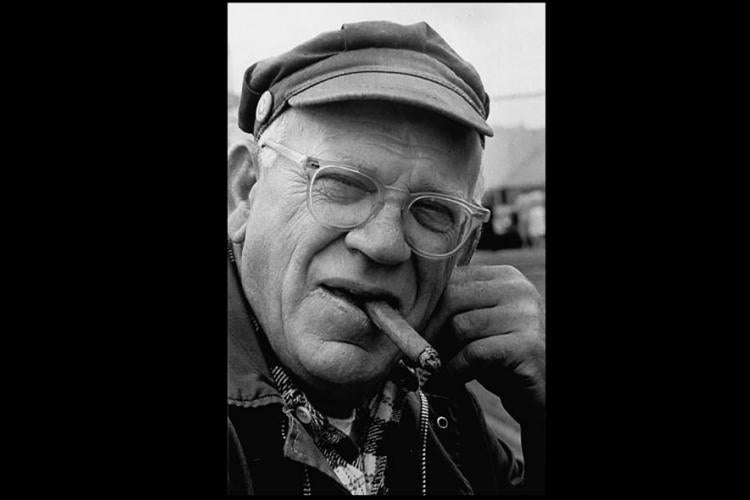

Greasy hair and a grimy face can be alarming to those who live with structured norms and ideas about what is proper and correct. Michael, a 49-year-old war veteran, has the look – smoky blue eyes, a long white beard and a tan, wrinkled face. He proves that the “homeless at heart” subculture is not exclusive to the younger generation.

“The war changed everything,” says Michael. “Before I went to Iraq, I felt people were much more conservative, respectful and genuine, but when I returned I was devastated by the values and morals that had seemed to have been tossed away.”

“Don’t get me wrong,” he says, stroking his beard, “there were many good changes that came from the war, but some of them were just too damn drastic for me.”

Michael struggled to cope with the changes in lifestyle and expectations in the progressive society, so he decided to abandon it and stick to what he thought made sense. He liberated himself by becoming homeless, sitting on the street corner with a simple request for some cash.

He chooses his own way and sees himself as an outsider, a divergent to today’s society, but an honorable one. Michael surmises that he is viewed as abnormal, mysterious or maybe even crazy; but, if he is any of those things, it is only because in one way or another we all are.

Allen

Allen has long, unkept blond hair that half covers his youthful face. His clothes, while not ragged or excessively dirty, clearly have stories to tell, of journeys they had made and homeless nights they have experienced.

If you passed Allen, holding a simple cardboard sign with the request for money or food, your heart would perhaps be moved, stirred by the sight of such a young person held captive by homelessness. But if you stopped for a momento to talk, your sympathies might turn to wonder and maybe even admiration.

Allen doesn’t see himself as a victim but rather as a victor. In his view, he has emerged from the societal trappings that engulf the average citizen, creating prisons from which true expression can never escape.

“Must we live in houses?” he asks. “Must we aim for roots and stability? May we be nomadic without living like the Bedouins in desert dwellings?”

Allen’s jungle is the streets, his home is the planet, his family is everyone he meets – but only if they can greet him without the preconception that he is a victim. His tattered sign money is not a cry for help, but an opportunity for other fellow time-travelers to share with him. Today he is helped, and tomorrow he will help.

Allen’s give-and-take philosophy has been carefully crafted by more than a year spent wandering across America, and he is not even American. With a family that would love to support him in any way he would allow, and an educational foundation that would gain him access to any institute of higher learning, it will forever be a mystery to imprisoned societal dwellers why he chooses to spend his nights in makeshift shelters, forest camps, city corners, or even the occasional hostel.

In an overpopulated world plagued by loneliness and estrangement, Allen finds the solitude he seeks, the friendships he chooses, and the family he needs among the homeless who fill our towns and cities, seen only when they want to be.

A different drummer

Among the many homeless who move among us, many are certainly forced into that lifestyle, but for some that life is a choice. To this subgroup, true freedom is only experienced outside the confines of societal norms that teach the necessity of responsibility, structure and gainful employment. In fact, it is the typical citizen who lacks understanding.

To these “homeless at heart,” a sense of belonging is found on the streets. Their family is fluid, their world is wide, their limitations are nonexistent and their only responsibility is to be true to self.

Surprisingly, the foundation of their lives is optimism and simplicity. They have no fear of tomorrow for they live in the now. They don’t view themselves as indolent nor as insane, but rather as divergent and adventurous. They do not need to be fixed; they just need to be understood.

Photo by Pam Black